French photographer. An only child of working-class parents, he was orphaned at an early age and went to sea. Determined to be an actor, he managed to study at the Conservatoire d’Art Dramatique in Paris for a year but was dismissed to finish his military service. Thereafter he acted for several seasons in the provinces but failed to distinguish himself and left the stage. An interest in painting but lack of facility led him to take up photography in the late 1880s. At this time photography was experiencing unprecedented expansion in both commercial and amateur fields. Atget entered the commercial arena. Equipped with a standard box camera on a tripod and 180×240 mm glass negatives, he gradually made some 10,000 photographs of France that describe its cultural legacy and its popular culture. He printed his negatives on ordinary albumen-silver paper and sold his prints to make a living. Despite the prevailing taste for soft-focus, painterly photography from c. 1890 to 1914, Atget remained constant in his straightforward record-making technique. It suited the notion he held of his calling, which was to make not art but documents.

By 1891 Atget had found a niche in the

Parisian artistic community selling to painters photographs of animals,

flowers, landscapes, monuments and urban views. In 1898 he began also to

specialize in documents of Old Paris, to satisfy the popular interest

in preserving the historic art and architecture of the capital. Working

alone, Atget accumulated a vast stock of photographs of old houses,

churches, streets, courtyards, doors, stairs, mantelpieces and other

decorative motifs. He marketed these images not only to artists but also

to architects, artisans, decorators, publishing houses, libraries and

museums. While Atget made his name doing this work, much of his

production was routine; his artistic fame came from his pursuit of this

approach.

The oeuvre demonstrates this variance

throughout; while Old Paris was Atget’s main theme, as he worked he

occasionally made photographs that seem more picturesque, imaginative or

formally inventive than others. Besides these individual, idiosyncratic

pictures, Atget also made some series of related images that denote a

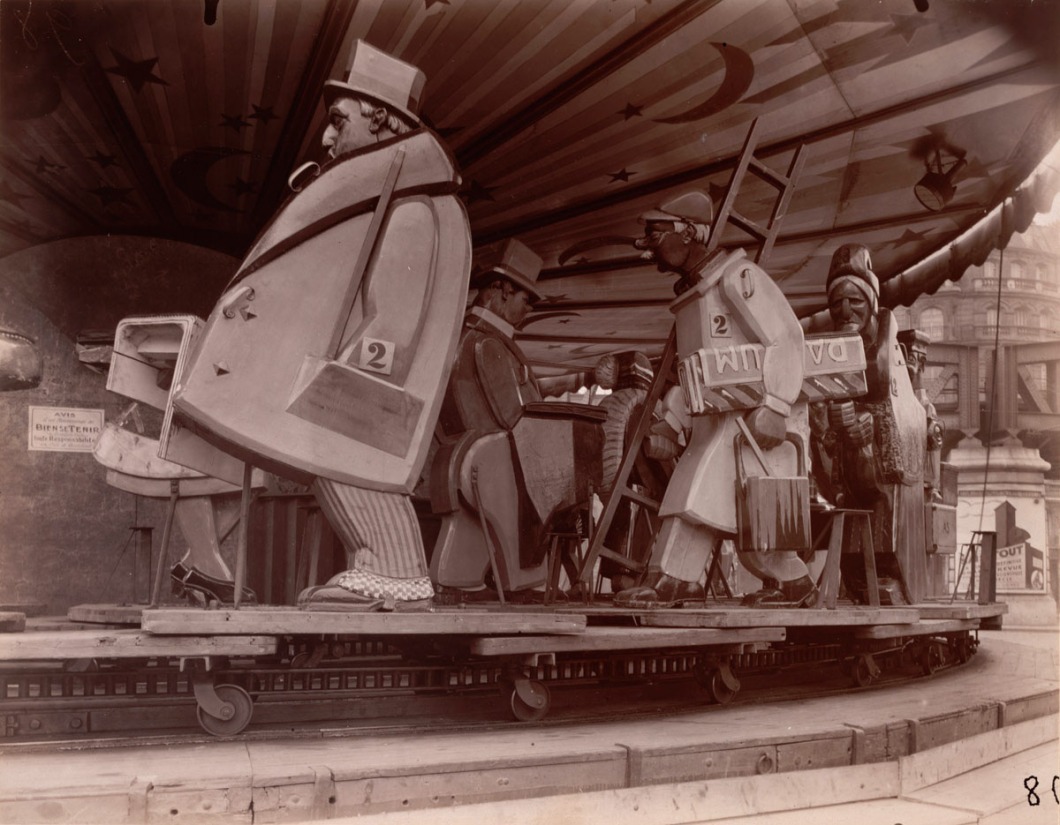

more vivid artistic presence. These include street scenes and the petits

métiers series (1898–1900); vehicles, bars, markets, boutiques,

gypsies, the quais and ‘zone’ (1910–14); prostitutes, shop displays and

street circuses (1921–7); and the churches, châteaux and gardens of the

Parisian environs, especially Versailles (from 1901), Saint-Cloud (from

1904) and Sceaux (1925; e.g. Parc de Sceaux, March, 8 a.m., New York,

MOMA).

The tendency towards personal autonomy

and free expression grew more marked as Atget’s career progressed.

Around 1910 he made seven carefully composed albums that he sold to the

Bibliothèque Nationale (see Nesbit), and in 1912 he broke off a

continuing assignment to survey the topography of the central wards of

the old city for the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His

pictorial production continued to fall during World War I, when he

photographed hardly at all.

In 1920 Atget sold most of his negatives

of Old Paris to the government; he had completed that section of his

work. While he retained an interest in the same genres of subject-matter

thereafter, he increasingly chose different aspects to depict. Whereas

his energies had been channelled into the relatively methodical

production of good, serviceable documents from 1898 to 1914, from 1922

until his death Atget more often made pictures whose usefulness as

reports to architects or decorators was questionable. The metaphorical

power, suggestive mood and pictorial innovation in the late work

appealed rather to an audience of poets and painters such as Man Ray,

Jean Cocteau, Robert Desnos (1900–45) and other Surrealists, who hailed

the photographer as a ‘naive’ whose straight yet sentient attitude had

analogies with their own.

In fact Atget’s art has little to do with

Surrealism; it expresses his acutely intelligent assessment of what he

valued through the medium of photography. The early morning light on a

Parisian street, the palpable atmosphere enveloping a pool at

Saint-Cloud and the disarming gesture of a mannequin reflected as if in

the street on a shop-window, were as directly and unselfconsciously

apprehended and with the same seriousness, humility and humanity as the

door-knockers and apple trees photographed early on. If the late works

reveal the artist’s own sensibility as much as the ostensible motif, it

was not Atget’s idea of his function that had changed but his vision of

what was worth photographing.

Atget’s best work is a poetic

transformation of the ordinary by a subtle and knowing eye well served

by photography’s reportorial fidelity. His transcendent, haunting works

transposed photography’s function from the arena of 19th-century

commercial documentation into the realm of art. This legacy,

posthumously heralded as paralleling the rejection by ‘art’

photographers of Pictorialism and the return to the straight,

unmanipulated approach, passed into the tradition of modern photographic

history through the efforts of the American photographer Berenice

Abbott, who met Atget in 1925 and who acquired his estate at his death.

It is now owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Maria Morris Hambourg

From Grove Art Online

From Grove Art Online

***** merci

AntwortenLöschen